The questions which the research team of RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA has continued to ask, included among other 1. Was he really called to the priesthood ab-initio? 2.Was he more useful to God and humanity as a priest or as a politician? These questions and more are addressed today to our teaming controversial political priests and bishops all over the world, particularly to those in our African continent, although the answers are blowing in the wind.

In this edition of our Newsletter RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA got a snapshot of La Croix Africa where it literarily painted a portrait of African priests whose political involvement has sparked controversy. They are Abbots Diamacoune Senghor from Senegal, Fulbert Youlou from the Republic of Congo and Barthélemy Boganda from the Central African Republic. RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY research team has added Moses Orshio Adasu, who was the Governor of Benue State in Nigeria.

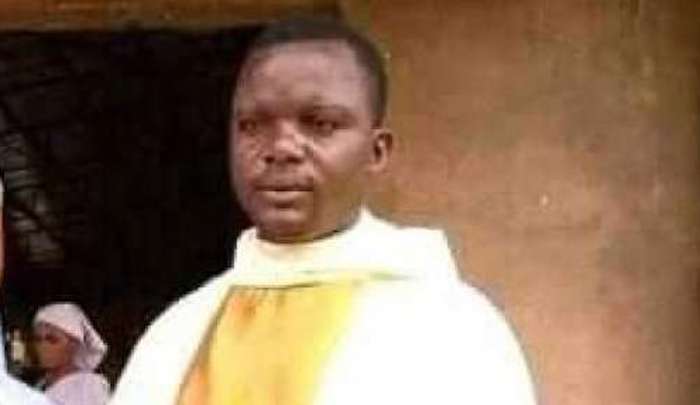

Today, RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY will take a critical look at the first indigenous priest of Ubangui-Chari, who was considered to be the founding father of the Central African Republic.

In 1938, the first indigenous priest of Ubangui-Chari – a French colony in central Africa – was ordained. His name was Barthélémy Boganda and he was aged 28 years old. This mythical man considered one of the fathers of Pan-Africanism was also the first black deputy of his country. He was the creator of the first local newspaper, founder of the independent party Mesan, first mayor of Bangui and president of the great Council of French Equatorial Africa (AEF). Information has it that he was the head of the first government of the Central African Republic.

At his funeral in 1959, Father Charles Feraille, a Spiritan religious, summed up his commitments in a very articulated sentence when he said, “Before becoming the elected representative of the people, Barthélémy Boganda had been elected by God.”

Childhood

The story of Bartholomew Boganda as was captured by our Burkina Faso correspondent, however, began in a tragic way. Born April 4, 1910 in Bobangui, in the equatorial forest, Barthélemy Boganda very early lost his parents. They were killed during punitive operations in a context where indigenous tribes were requisitioned for forced labor for the benefit of French companies.

He was immediately adopted by Lieutenant Meyer, administrator of Mbaïki (Southwest), which at the time depended on the Middle Congo. He later ended up staying with Father Gabriel Herriau, of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit, superior of the Catholic Mission of Bétou whose field of apostolate extended as far as Mbaïki. For 18 years, he will be trained by Spiritan missionaries. After attending primary school in Mbaïki, the Spiritans sent young Boganda to DR Congo, to the Minor Seminary of Kisantu, 120 km south of Kinshasa. He then continued his training as a Seminarian in Brazzaville.

In 1931, Bishop Marcel Grandin, apostolic prefect of Ubangui-Chari, sent Boganda, who was then teaching catechesis in Bangui, Yaoundé, Cameroon, to complete his formation. He was the first Oubanguien to finish his secondary studies and the first bachelor of this colony.

He was ordained a priest 7 years later, in 1938. FThe firstnative priest of Ubangi-Chari, Barthélémy was sent on a mission to Bambari in 1941. In his understanding, evangelization is inseparable from education and social action. He applies this idea to Grimari, a secondary mission dependent on Bamabari, of which he was responsible. Indeed, these methods were fruitful since Masses and catechesis courses attract more and more people. But the success of Boganda, a secular priest, is not to the liking of the French Spiritan missionaries who settled in Bambari and who had until then failed in Grimary. To this envy was added racism that was difficult for the young priest. “When Boganda returned from Grimary, he did not eat with his fellow white priests but with the cook, in the kitchen,” as was reported by Central African historian Maurice Saragba. (3)

Beginnings in politics

Unlike Father Fulbert Youlou, from Congo-Brazzaville, Barthélémy was encouraged by his superiors to get into politics. In November 1946, he stood for the legislative elections of the second college in the Assembly of the French Union under the label of the Popular Republican Movement (MPR). In this regard, Monsignor Marcel Grandin wrote to his friend Father Lecomte: “We are launching into Oubangui: but there are so many anti-French gueulards that I did not hesitate to launch the abbot as an adversary to the Communists, Socialists., Sfio, etc., who believe that we are muzzled sheep” (1).

Barthélémy Boganda was elected deputy. But disappointed by French overseas policy, he neglected his parliamentary duties and launched the Société coopérative de l’Oubangui-Lobaye-Lessé (Socoulolé), which organized indigenous producers in order to demand better remuneration for their products. The initiative clashes with deputies and colonial administrators who are united against this project.

In 1949, Boganda created his own political party, the Mesan, which aspires to “feed, clothe, heal, educate and house” Africans.

The success and strong temperament of this young priest with a messianic feel are beginning to cause concern within the Church and in the French political world.

Departure from the clerical state and marriage.

The break with his diocese was consummated in 1949 when Boganda chose to live in a conjugal relationship with a Frenchwoman, his parliamentary assistant, Michelle Jourdain. On November 25, 1949, Bishop Joseph Cucherousset, successor to Bishop Grandin, officially suspended him. Boganda can no longer exercise his priestly functions in public or wear the cassock.

In a letter to his bishop, he explains the circumstances that led to this situation. “I was suspended by political, racist, and arbitrary measures far more than religious,” he wrote. While acknowledging that he deserved the canonical penalties to which he was subjected, Boganda questions his bishop about the circumstances which led to this result. “If in our missions, I had not been exasperated by attitudes, injustices, insults, of which ‘dirty nigger pig’ is only one example among a thousand, I would perhaps never have thought of living with a Frenchwoman from the metropolis to upset my racist colleagues and they are legion”. (2) he points out. “I think it is more worthy to live with a woman than to make a wish that you constantly miss,” he added.

In 1950, the former priest married Michelle Jourdain who was expecting her first child.

Permanently suspended by the Church, Boganda responds to his bishop. “The habit does not make the monk; the cassock does not make the apostle or the priest. I remain the apostle of Ubangi and of the Church “.

But the former priest never breaks with the Catholic Church, whose doctrine inspired his commitment as a leading political actor.

Political success and brutal death.

With a solid reputation, Boganda became mayor of Bangui in 1956 and his Mesan party held all 50 seats to be filled for the 1957 local elections. However, he chose not to enter the first local government resulting from this election. He was limited in participating in the nomination of its members but he insisted that positions be allocated to its party and to civilian figures.

In the same 1957, he became president of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa (AEF), an essentially honorary position. Defender of Pan-Africanism, he dreams of the United States of Latin Africa which would have brought together not only the countries of the AEF but also Angola and the Belgian Congo (DRC).

On December 1, 1958, the Central African Republic was proclaimed. It covered the territory of the former colony of Ubangui-Chari. Boganda became the president of the government. In this capacity, he set up the institutions of the country.

He died in a plane crash on March 29, 1959, while traveling from Berberati to Bangui. He was 48 years old. He is considered the founding father of the Central African Republic.

Depuis La Croix Africa, le Correspondant de RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA, basé à Aougadougou, la capitale du Burkina, a rassemblé une histoire très intéressante qui mérite d’être publiée dans notre Newsletter. L’histoire raconte que Barthélémy Boganda, fut le premier prêtre d’Ubangui-Chari et le père fondateur de la République centrafricaine. Notre correspondant a compris que Boganda a quitté la prêtrise à un moment de son parcours historique à travers la vie et a rejoint la politique. Ce grand homme nommé Barthélémy Boganda a fini par devenir l’ancien président de la République centrafricaine.

Les questions que l’équipe de recherche de RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA n’a cessé de se poser, entre autres 1. A-t-il vraiment été appelé au sacerdoce ab-initio ? 2. Était-il plus utile à Dieu et à l’humanité en tant que prêtre ou en tant qu’homme politique ? Ces questions et bien d’autres s’adressent aujourd’hui à notre équipe de prêtres et d’évêques politiques controversés du monde entier, en particulier à ceux de notre continent africain, bien que les réponses soufflent dans le vent.

Dans cette édition de notre Newsletter RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA a obtenu un instantané de La Croix Africa où elle a littéralement peint un portrait de prêtres africains dont l’engagement politique a suscité la controverse. Il s’agit des abbés Diamacoune Senghor du Sénégal, Fulbert Youlou de la République du Congo et Barthélemy Boganda de la République centrafricaine. L’équipe de recherche de RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY a ajouté Moses Orshio Adasu, qui était le gouverneur de l’État de Benue au Nigeria.

Aujourd’hui, RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY portera un regard critique sur le premier prêtre indigène d’Ubangui-Chari, qui était considéré comme le père fondateur de la République centrafricaine.

En 1938, le premier prêtre indigène de l’Ubangui-Chari – une colonie française d’Afrique centrale – est ordonné. Il s’appelait Barthélémy Boganda et il était âgé de 28 ans. Cet homme mythique considéré comme l’un des pères du panafricanisme fut aussi le premier député noir de son pays. Il a été le créateur du premier journal local, fondateur du parti indépendant Mesan, premier maire de Bangui et président du grand Conseil de l’Afrique équatoriale française (AEF). Selon les informations, il était le chef du premier gouvernement de la République centrafricaine.

Lors de ses obsèques en 1959, le père Charles Feraille, religieux spiritain, résumait ses engagements dans une phrase très articulée lorsqu’il disait : « Avant de devenir l’élu du peuple, Barthélémy Boganda avait été élu par Dieu.

Enfance

L’histoire de Bartholomée Boganda telle qu’elle a été capturée par notre correspondant au Burkina Faso, cependant, a commencé d’une manière tragique. Né le 4 avril 1910 à Bobangui, dans la forêt équatoriale, Barthélemy Boganda perd très tôt ses parents. Ils ont été tués lors d’opérations punitives dans un contexte où des tribus indigènes étaient réquisitionnées pour des travaux forcés au profit d’entreprises françaises.

Il est aussitôt adopté par le lieutenant Meyer, administrateur de Mbaïki (Sud-Ouest), qui dépend à l’époque du Moyen Congo. Il a fini par séjourner chez le Père Gabriel Herriau, de la Congrégation du Saint-Esprit, supérieur de la Mission catholique de Bétou dont le champ d’apostolat s’étendait jusqu’à Mbaïki. Pendant 18 ans, il sera formé par des missionnaires spiritains. Après avoir fréquenté l’école primaire à Mbaïki, les Spiritains ont envoyé les jeunes Boganda en RD Congo, au Petit Séminaire de Kisantu, à 120 km au sud de Kinshasa. Il poursuit ensuite sa formation de séminariste à Brazzaville.

En 1931, Mgr Marcel Grandin, préfet apostolique de l’Ubangui-Chari, envoya Boganda, qui enseignait alors la catéchèse à Bangui, Yaoundé, Cameroun, pour compléter sa formation. Il fut le premier Oubanguien à terminer ses études secondaires et le premier bachelier de cette colonie.

Il est ordonné prêtre 7 ans plus tard, en 1938. Premier prêtre originaire d’Ubangi-Chari, Barthélémy est envoyé en mission à Bambari en 1941. Selon lui, l’évangélisation est indissociable de l’éducation et de l’action sociale. Il applique cette idée à Grimari, une mission secondaire dépendante de Bamabari, dont il était responsable. En effet, ces méthodes ont été fructueuses puisque les messes et les cours de catéchèse attirent de plus en plus de monde. Mais le succès de Boganda, prêtre séculier, n’est pas du goût des missionnaires spiritains français installés à Bambari et qui avaient jusqu’alors échoué à Grimary. A cette envie s’est ajouté un racisme difficile pour le jeune prêtre. “Quand Boganda est revenu de Grimary, il n’a pas mangé avec ses confrères prêtres blancs mais avec le cuisinier, dans la cuisine”, comme l’a rapporté l’historien centrafricain Maurice Saragba. (3)

Débuts en politique

Contrairement au père Fulbert Youlou, originaire du Congo-Brazzaville, Barthélémy a été encouragé par ses supérieurs à se lancer en politique. En novembre 1946, il se présente aux élections législatives du second collège de l’Assemblée de l’Union française sous l’étiquette du Mouvement républicain populaire (MPR). A ce propos, Monseigneur Marcel Grandin écrit à son ami le Père Lecomte : « Nous nous lançons dans l’Oubangui : mais il y a tellement de gueulards anti-français que je n’ai pas hésité à lancer l’abbé en adversaire des communistes, socialistes., Sfio , etc., qui croient que nous sommes des brebis muselées » (1).

Barthélémy Boganda a été élu député. Mais déçu par la politique française d’outre-mer, il néglige ses fonctions parlementaires et lance la Société coopérative de l’Oubangui-Lobaye-Lessé (Socoulolé), qui organise les producteurs indigènes afin d’exiger une meilleure rémunération de leurs produits. L’initiative se heurte aux députés et administrateurs coloniaux qui s’unissent contre ce projet.

En 1949, Boganda crée son propre parti politique, le Mesan, qui aspire à « nourrir, habiller, soigner, éduquer et loger » les Africains.

Le succès et le fort tempérament de ce jeune prêtre au caractère messianique commencent à inquiéter au sein de l’Église et du monde politique français.

Sortie de l’état clérical et mariage.

La rupture avec son diocèse est consommée en 1949 lorsque Boganda choisit de vivre en couple avec une Française, son assistante parlementaire, Michelle Jourdain. Le 25 novembre 1949, Mgr Joseph Cucherousset, successeur de Mgr Grandin, le suspend officiellement. Boganda ne peut plus exercer ses fonctions sacerdotales en public ni porter la soutane.

Dans une lettre à son évêque, il explique les circonstances qui ont conduit à cette situation. “J’ai été suspendu par des mesures politiques, racistes et arbitraires bien plus que religieuses”, écrit-il. Tout en reconnaissant qu’il méritait les peines canoniques auxquelles il a été soumis, Boganda interroge son évêque sur les circonstances qui ont conduit à ce résultat. « Si dans nos missions, je n’avais pas été exaspéré par des attitudes, des injustices, des insultes, dont le ‘sale cochon nègre’ n’est qu’un exemple parmi mille, je n’aurais peut-être jamais songé à vivre avec une française de la métropole pour bouleverser mes collègues racistes et ils sont légion ». (2) précise-t-il. “Je pense qu’il est plus digne de vivre avec une femme que de faire un vœu qui vous manque constamment”, a-t-il ajouté.

En 1950, l’ancien prêtre épousa Michelle Jourdain qui attendait son premier enfant.

Suspendu définitivement par l’Église, Boganda répond à son évêque. « L’habit ne fait pas le moine ; la soutane ne fait pas l’apôtre ou le prêtre. Je reste l’apôtre de l’Ubangi et de l’Église ».

Mais l’ancien prêtre ne rompt jamais avec l’Église catholique, dont la doctrine a inspiré son engagement en tant qu’acteur politique de premier plan.

Succès politique et mort brutale.

Fort d’une solide réputation, Boganda devient maire de Bangui en 1956 et son parti Mesan détient les 50 sièges à pourvoir pour les élections locales de 1957. Cependant, il a choisi de ne pas entrer dans le premier gouvernement local issu de cette élection. Il a été limité dans sa participation à la nomination de ses membres mais il a insisté pour que les postes soient attribués à son parti et à des personnalités civiles.

Dans le même 1957, il devient président du Grand Conseil de l’Afrique équatoriale française (AEF), poste essentiellement honorifique. Défenseur du panafricanisme, il rêve des États-Unis d’Afrique latine qui auraient réuni non seulement les pays de l’AEF mais aussi l’Angola et le Congo belge (RDC).

Le 1er décembre 1958, la République centrafricaine est proclamée. Il couvrait le territoire de l’ancienne colonie d’Ubangui-Chari. Boganda est devenu le président du gouvernement. A ce titre, il a mis en place les institutions du pays.

Il est mort dans un accident d’avion le 29 mars 1959, alors qu’il voyageait de Berberati à Bangui. Il avait 48 ans. Il est considéré comme le père fondateur de la République centrafricaine.

Da La Croix Africa, o Correspondente da RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA, com sede em Aougadougou, capital de Burkina, reuniu uma história muito interessante que vale a pena publicar em nosso Boletim Informativo. A história conta que Barthélémy Boganda foi o primeiro sacerdote de Ubangui-Chari e o fundador da República Centro-Africana. Nosso correspondente concluiu que Boganda deixou o sacerdócio em um momento de sua jornada histórica pela vida e ingressou na política. Este grande homem chamado Barthélémy Boganda acabou finalmente como o ex-presidente da República Centro-Africana.

As perguntas que a equipe de pesquisa da RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA continuou a fazer, incluindo entre outras 1. Ele foi realmente chamado ao sacerdócio ab initio? 2. Ele foi mais útil a Deus e à humanidade como sacerdote ou como político? Estas e outras questões são dirigidas hoje a nossa equipe polêmica de padres e bispos políticos em todo o mundo, especialmente para aqueles em nosso continente africano, embora as respostas estejam soprando no vento.

Nesta edição do nosso Boletim RECOWACERAO NEWS AGENCY, RECONA obteve um instantâneo de La Croix Africa, onde pintou literariamente um retrato de padres africanos cujo envolvimento político gerou polêmica. Eles são os Abades Diamacoune Senghor do Senegal, Fulbert Youlou da República do Congo e Barthélemy Boganda da República Centro-Africana. A equipe de pesquisa da AGÊNCIA DE NOTÍCIAS RECOWACERAO acrescentou Moses Orshio Adasu, que era o governador do Estado de Benue na Nigéria.

Hoje, a AGÊNCIA DE NOTÍCIAS RECOWACERAO fará um olhar crítico sobre o primeiro sacerdote indígena de Ubangui-Chari, considerado o pai fundador da República Centro-Africana.

Em 1938, o primeiro sacerdote indígena de Ubangui-Chari – uma colônia francesa na África Central – foi ordenado. Seu nome era Barthélémy Boganda e ele tinha 28 anos. Este homem mítico considerado um dos pais do pan-africanismo foi também o primeiro deputado negro de seu país. Foi o criador do primeiro jornal local, fundador do partido independente Mesan, primeiro prefeito de Bangui e presidente do grande Conselho da África Equatorial Francesa (AEF). Segundo informações, ele foi o chefe do primeiro governo da República Centro-Africana.

No seu funeral de 1959, o padre Charles Feraille, religioso espiritano, resumiu os seus compromissos numa frase muito articulada ao dizer: “Antes de se tornar representante eleito do povo, Barthélémy Boganda tinha sido eleito por Deus”.

Infância

A história de Bartolomeu Boganda, conforme capturada por nosso correspondente em Burkina Faso, no entanto, começou de forma trágica. Nascido em 4 de abril de 1910 em Bobangui, na floresta equatorial, Barthélemy Boganda perdeu seus pais muito cedo. Eles foram mortos durante operações punitivas em um contexto em que tribos indígenas foram requisitadas para trabalhos forçados em benefício de empresas francesas.

Ele foi imediatamente adotado pelo Tenente Meyer, administrador de Mbaïki (sudoeste), que na época dependia do Médio Congo. Posteriormente, acabou ficando com o padre Gabriel Herriau, da Congregação do Espírito Santo, superior da Missão Católica de Bétou, cujo campo de apostolado se estendia até Mbaïki. Durante 18 anos, ele será formado por missionários espiritanos. Depois de frequentar a escola primária em Mbaïki, os espiritanos enviaram a jovem Boganda para a República Democrática do Congo, para o Seminário Menor de Kisantu, 120 km ao sul de Kinshasa. Ele então continuou sua formação como seminarista em Brazzaville.

Em 1931, o bispo Marcel Grandin, prefeito apostólico de Ubangui-Chari, enviou Boganda, que então ensinava catequese em Bangui, Yaoundé, Camarões, para completar sua formação. Foi o primeiro Oubanguien a terminar os estudos secundários e o primeiro bacharel desta colônia.

Foi ordenado sacerdote 7 anos depois, em 1938. FPrimeiro sacerdote de Ubangi-Chari, Barthélémy, foi enviado em missão a Bambari em 1941. Para ele, evangelização é indissociável da educação e da ação social. Ele aplica essa ideia a Grimari, uma missão secundária dependente de Bamabari, da qual ele era responsável. De fato, esses métodos foram frutíferos, pois as missas e os cursos de catequese atraem cada vez mais pessoas. Mas o sucesso de Boganda, um padre secular, não agradou aos missionários espiritanos franceses que se estabeleceram em Bambari e que até então fracassaram em Grimary. A essa inveja foi adicionado o racismo que era difícil para o jovem padre. “Quando Boganda voltou de Grimary, ele não comia com seus companheiros padres brancos, mas com o cozinheiro, na cozinha”, como foi relatado pelo historiador centro-africano Maurice Saragba. (3)

Começos na política

Ao contrário do padre Fulbert Youlou, do Congo-Brazzaville, Barthélémy foi incentivado por seus superiores a entrar na política. Em novembro de 1946, concorreu às eleições legislativas do segundo colégio da Assembleia da União Francesa sob o rótulo de Movimento Republicano Popular (MPR). A este respeito, Monsenhor Marcel Grandin escreveu ao seu amigo padre Lecomte: “Estamos a lançar-nos em Oubangui: mas há tantos gueulards anti-franceses que não hesitei em lançar o abade como adversário dos comunistas, socialistas., Sfio , etc., que acreditam que somos ovelhas amordaçadas ”(1).

Barthélémy Boganda foi eleito deputado. Mas decepcionado com a política ultramarina francesa, ele negligenciou seus deveres parlamentares e lançou a Société coopérative de l’Oubangui-Lobaye-Lessé (Socoulolé), que organizou produtores indígenas para exigir melhor remuneração por seus produtos. A iniciativa se choca com deputados e administradores coloniais que se unem contra o projeto.

Em 1949, Boganda criou seu próprio partido político, o Mesan, que aspira a “alimentar, vestir, curar, educar e abrigar” os africanos.

O sucesso e o temperamento forte deste jovem sacerdote com um sentimento messiânico começam a causar preocupação na Igreja e no mundo político francês.

Afastamento do estado clerical e casamento.

O rompimento com a diocese foi consumado em 1949, quando Boganda decidiu viver em uma relação conjugal com uma francesa, sua assistente parlamentar, Michelle Jourdain. Em 25 de novembro de 1949, o bispo Joseph Cucherousset, sucessor do bispo Grandin, o suspendeu oficialmente. Boganda não pode mais exercer suas funções sacerdotais em público ou usar batina.

Em uma carta ao bispo, ele explica as circunstâncias que levaram a essa situação. “Fui suspenso por medidas políticas, racistas e arbitrárias muito mais do que religiosas”, escreveu ele. Embora reconheça que merece as penalidades canônicas às quais foi submetido, Boganda questiona seu bispo sobre as circunstâncias que levaram a esse resultado. “Se em nossas missões eu não tivesse me exasperado com atitudes, injustiças, insultos, dos quais ‘porco negro sujo’ é apenas um exemplo entre mil, talvez nunca tivesse pensado em morar com uma francesa da metrópole para incomodar minha colegas racistas e eles são legião ”. (2) ele aponta. “Acho que vale mais a pena morar com uma mulher do que fazer um desejo que você sempre perde”, acrescentou.

Em 1950, o ex-padre casou-se com Michelle Jourdain, que estava grávida do primeiro filho.

Suspenso permanentemente pela Igreja, Boganda responde ao seu bispo. “O hábito não faz o monge; a batina não faz o apóstolo nem o sacerdote. Continuo a ser apóstolo de Ubangi e da Igreja”.

Mas o ex-padre nunca rompe com a Igreja Católica, cuja doutrina inspirou seu compromisso como ator político de destaque.

Sucesso político e morte brutal.

Com uma sólida reputação, Boganda se tornou prefeito de Bangui em 1956 e seu partido Mesan ocupou todas as 50 cadeiras a serem preenchidas nas eleições locais de 1957. No entanto, ele optou por não entrar no primeiro governo local resultante desta eleição. Ele estava limitado a participar da nomeação de seus membros, mas insistiu que os cargos fossem atribuídos ao seu partido e a figuras civis.

No mesmo 1957, tornou-se presidente do Grande Conselho da África Equatorial Francesa (AEF), um cargo essencialmente honorário. Defensor do pan-africanismo, sonha com os Estados Unidos da África Latina que teriam reunido não só os países da AEF mas também Angola e o Congo Belga (RDC).

Em 1 ° de dezembro de 1958, foi proclamada a República Centro-Africana. Cobriu o território da ex-colônia de Ubangui-Chari. Boganda se tornou o presidente do governo. Nessa qualidade, ele montou as instituições do país.

Ele morreu em um acidente de avião em 29 de março de 1959, durante uma viagem de Berberati para Bangui. Ele tinha 48 anos. Ele é considerado o pai fundador da República Centro-Africana.

- RECOWA-CERAO WELCOMES TWO NEW BISHOPS - July 26, 2024

- TODAY WE ARE TAKING UP THE THIRD SEGMENT IN OUR SERIES - July 26, 2024

- CHARACTERISTICS OF GREAT LEADERS SHARED BY A USA AUTHOR - July 25, 2024